My thoughts on Muhammad Ali’s death lead me first to March 8, 1971.

It was a Monday night. I was 12, lying in bed with a transistor radio, crazy with anticipation.

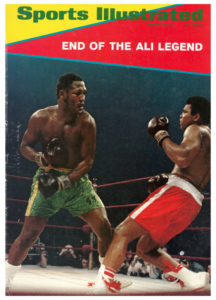

Ali and Joe Frazier, the heavyweight champion, were fighting that night at Madison Square Garden. It is hard to overstate the hype that preceded that matchup of two undefeated heavyweights. The spectacle of boxing was still huge in the country, inexplicably huge to someone like my kids, and almost hard to believe for me now. Ali was of course a mega-personality unlike any sports had known, perhaps other than Babe Ruth in his time. But Ali’s skills were rusty from his suspension for refusing military service; this was only his third bout back. And Frazier was a stalking, vicious champion with a thunderous left hook.

The fight wasn’t on television or radio. Closed-circuit TV was the medium of the era for big boxing events. It was a cash cow. Fans would buy a ticket into a stadium or another venue to watch the broadcast. So on my radio, tuned to an AM music station, the deejay broke in after every round to report the latest from the broadcast, probably Philly’s Spectrum. I have a thought that the voice was that of George Michael, who was huge in Philly and later moved on to larger fame in Washington, D.C. But even if it wasn’t, I know I hung on every urgent word.

The record shows that Ali surprised Frazier early, but Frazier bore into Ali through the middle rounds. I don’t remember the specifics of the scorecard except that Frazier was by far the aggressor. Early in the 15th and final round, that aggression paid off. Frazier bashed a left into Ali’s jaw and decked him, stunning news across the AM band. The replay I later saw of the knockdown did the word-picture justice — Ali’s right leg jackknifed, the red tassles splayed on his white boot, flat on his back.

Ali survived the round and the fight went to completion. That seems impossible for heavyweights of this magnitude. Also impossible is the event matched and exceeded its massive hype. Frazier won in a unanimous decision. Ali, of course, went on to defeat Frazier twice in two bouts, brutal affairs that contributed to the inexorable physical decline suffered by each before their deaths.

Other than being in the stadium when he lit the 1996 Olympic flame in Atlanta, I sort of met Ali once, long after his retirement and well into his struggle with Parkinson’s. He had to appear in a Norfolk court to give a deposition in a civil suit, as I recall. Word leaked that Ali would be there, and the editors quickly dispatched me and another reporter across the street to the building.

We found Ali and a small entourage waiting in the lobby outside the courtroom. Just like that, the most famous person in the world at one time, just sitting there. Ali said nothing, but probably on his word, the attorneys were good with us just hanging around, soaking in the scene.

As he often did in public, Ali quietly performed a couple of magic tricks – one with a disappearing handkerchief, another where he turned his back and suddenly appeared to be levitating. I got his autograph, certainly the only time in a long career that I broke that journalistic cardinal rule. Then, it was over, and we were on our way.

I’ve enjoyed the montages and reminiscences since his death last Friday, testimonials to his impossibly indescribable presence. This Friday’s memorial service in Louisville, scheduled to be laden with dignitaries from all walks, will be impossibly moving.

As with anything involving Ali, ever, the anticipation is thick.

Chavez raced to the besieged, burning harbor and did not leave again for more than a week. Then, he spent the next half-century avoiding discussions of the horrors he witnessed.

Chavez raced to the besieged, burning harbor and did not leave again for more than a week. Then, he spent the next half-century avoiding discussions of the horrors he witnessed.